|

|

Shova

returns in her new sari, this one silk and gilded with rich gold and

green. Her tuile veil is replaces by a traditional wedding veil, criss-crossed

with shiny gold foil trim. A white khatta, prayer scarf, is placed over

both their shoulders, but it falls into his lap.

The rituals

continue...the new couple following the priest's lead. Tossing rice,

water, and other things into the fire, as instructed. At one point, they

stand up and with Tika behind her, his hands around her and clasping

hers, together they throw rice down onto the fire.

Then they walk three

times around the small canopy, stopping at each cardinal point.

At

times, she leaves and only Tika remains to carry out the rituals as he

prepares himself to take on this new responsibility.

At

times, near tears, she tries to retreat into her veil, but her sister

pulls it away and off her face.

Finally,

the moment everyone has been waiting for. A white sheet is folded into a

long ramp and one end held at her forehead. Tika is given sindoor,

special red-orange powder in his palm. Starting at the far end of the

sheet, the sindoor is ritually spread along the sheet up to her forehead

and then pressed into the part of her hair. This is repeated three

times, and the most important part of a wedding ceremony. They are now

married. Everything else is fluff. If, at any time, a man places sindoor

in the part of a women's hair, they are absolutely married in Nepalese

culture. Once married, all Nepalese women will wear sindoor in the part

of their hair for the rest of their lives, until their husband dies,

then they must stop. Widows may never wear red clothes or receive a red

tika. Instead they opt for white, blue and yellow with only white and

yellow tikkas.

Her

sister takes out a small hankerchief, folds into a square and pins it

into her hair over the sindoor, covering it completely. Her father or

male relatives are not allowed to see it on her forehead on that day,

representing as such, her entrance into womanhood.

Finally,

the rituals are over. A light rain as started. The men begin to take out

the chairs and table at which they sat, and load them into the waiting

truck. Other items are brought out from the house. A darage, a large

metal locker that Nepalis use for clothing storage as home do not have

closets, a fan, copper water vessels, a dining table and chairs, and a

cow, a God in their new home. These things represent her dowry. Tika,

for his part, tried to refuse the dowry, but they insisted on some

things. Weddings I have been to recently in Kathmandu were completely

over-the-top with dowries that soared above $10,000 US dollars. This is

Nepal's new monied class. You have to pay for membership.

Shova

is now crying. Her three younger sisters lead her into the van and stay

with her, trying to reassure her, wipe away her tears while the final

preparations are made to leave. Tika comes and we load into the van. She

is staring out the window at her home, as we pull away. The van, the

bus, and the truck now laden down.

The

journey is slow now because of the rain which has picked up. The road to

the village side is wet and muddy. We reach the base of the mountain and

begin a gruelingly slow journey back up to Tika's home. A deep quiet has

come over the group. There is not the same singing as before. Having

left late, it is now dark and the trail completely unlighted. Sarita, my

Nepali sister, is walking with Shova trying to hold an umbrella over her

head and lead her across the unfamiliar terrain. In her platform shoes,

she almost falls many times and that only increases her crying. Sarita

brought for me an extra umbrella, which I share with the video-man. He

is hogging it all for his camera, so I walk ahead and get drenched.

We

finally arrive back at Tika's home. The rain has driven the women into

the house and they are spilling out into the shelter of the front porch.

They are still singing and dancing. As the first of our group straggle

in, they bombard us with questions. But I just sit on the floor

exhausted from the climb. Soon, Shova and Tika arrive and she is

immediately hussled into the house to an area already prepared for their

arrival. They are seated on the floor and the women gather around

tightly, trying to see her face, to see her beauty.

The

married women, one by one, bless the new couple with tikka and envelopes

of money, but with a new twist. Each time, the new bride must get up and

genuflect, kneeling all the down and touching her forehead to the

women's feet to show great respect for the commnity of women, of which

she is the newest member.

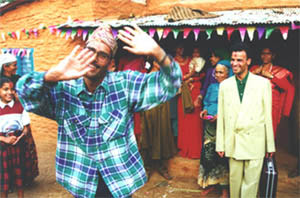

Me, center right,

and the mother's committee of Chitopani, as they like to be known.

Once

all the women had blessed them, the ritual was finally over. They ate a

meal together while people milled all about, more casual now. Outside, the women were still

dancing and singing, as

they had been all day, and

this time, the men of

the entourage joined in.

The rain abated and people were in no mood to stop. Singing contests

began, with groups of men challenging women. A chorus would be sung by

all, then one side would sing a verse, in flirtation, followed by the

chorus. Then the member of the other side would have to retort, the

saucier the better. The madal, a Nepali drum, was played during the

chorus and members of both sides would spontaneously jump up and dance,

then pause and eagerly await the next raunchy verse.

Inside

the house, away from all the festivities, sat Shova. She looked sad and

forlorn, sitting off to one side. Tika was outside celebrating, and all

around her the women were chattering like birds, but not to her. I tried

to cheer her up, and spoke to her in my broken Nepali until I got a

laugh out of her. From that moment on, she clung to me like a life line.

Outside, a Gurung youth group had arrived to perform. Together we went

outside and watched them. Tika came over and seemed relieved at my

presence, because it gave her comfort in a difficult time. FInally, I

grew weary and asked Sarita where I should sleep. People seemed content

to bunk on open ground. I just wanted to know where my piece of earth

was. We went to Tika's childhood room and talked awhile, the three of

us. Then, Shova looked at me and said "Tapaii masanga sutnus."

Will you please sleep with me? HUH? I struggled to make

sure I understood her

properly. When she repeated the request, I searched frantically for the

correct nepali words to reply. Finally, I blurted out "Tapaii

shriman, dherai ris lagyo" Your husband will be very angry! I looked

to Sarita for help. 'Ke Garne?' What to do? She said,

go ahead. Shova was too scared to sleep with her husband, so, on this

wedding night, I slept with the

bride instead. That has got to

be a faux pas in any culture

but who am

I to say...

The next day dawned

and the festivities continued. The local men cooked a huge meal and the

women served it.

After

eating, Tika and Shova prepared to leave to go to his home in Lakeside.

Everyone turned out to say goodbye, and some were so happy...

they

burst in dance. Look Devi Uncle go.

I

finally got Shova to smile for a photo. Here she is with her new husband

Tika and Tika's mother.

And

the bride and groom rode off into the sunset...

side

saddle of course...

P.S.

I am glad to note that their relationship was consumated pretty quick

because exactly nine months later she gave birth to little Sanu, a sweet

baby girl.

Culture | 1

| 2

| 3 |